Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Monday, December 27, 2010

Young Things

We may be young things, but we're not too young; we're young enough. We're young enough to understand the beauty and pain of love. We're young enough to be sympathetic to those who need our compassion and blunt to those who can't stand heavy sentiments. We're young enough to be brutally honest or creatively cunning. We're young enough to practice true loyalty, to make family out of friends, to be brave enough to discover ourselves. We are young things and we know how to live with passion and excitement and conviction. Who is anyone to tell you to be anything other than young and adventurous? Go be a young thing with pride in all that you are and all that you create.

Go Find Yourself

The thing about going away someplace is that you change. Life happens. You meet people, you experience things. Everything is somehow completely different. The problem with that lies in coming home because you expect people to notice. You want them to just see the changes in you and understand how to function in your new life, but they're expecting everything to be exactly the same as before. The important part is to recognize you've changed and embrace it. Keep changing. There will never be one complete and absolute version of who you are so go out into the world and find yourself and then find yourself again. Change is beautiful. Change is constant. Enjoy it even if no one else understands.

Friday, December 24, 2010

Thursday, December 23, 2010

A Room of One’s Own (1929): A Review

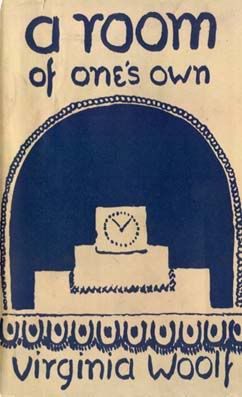

This is the first edition copy of A Room of One’s Own, published by the Hogarth Press. Another lovely cover by Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell. For those of you unfamiliar with the Hogarth Press, it was a small printing press founded in 1917 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf. One could imagine how convenient the press proved in allowing Virginia to publish small sketches and essays here and there—such as this one for instance.

A Room of One’s Own has become vastly popular since its original publication in 1929. The penguin group has recently even decided to fabricate mugs and beach towels, decorated with their own grape-colored edition of Virginia’s essay. For, although over a hundred pages, A Room of One’s Own is characteristically an essay. Here’s Virginia again, innovating literary forms, saying, ‘it can be done, it should be done.’

Yet this bold little book didn’t exactly begin as an essay. It was put together, so I read, “from two papers read to the Arts Society at Newnham and the Odtaa at Girton” (two women's colleges at Cambridge University in 1929).

“A woman,” Mrs. Woolf writes, “must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” This is her essay’s central argument. But how did Mrs. Woolf come to arrive at such a conclusion? What’s all this about women and fiction and rooms?

A Room of One’s Own scrutinizes the limited roles women have been condemned to inhabit in patriarchal societies, and the effects that these limitations have had on them and their art—namely, the art of writing. Throughout history women artists have had to contend with extraordinary amounts of opposition—indeed hostility—to pursue their art. One recalls the stories: ‘It is not your place to produce art,’ said a certain Elizabethan gentleman to his lady, upon discovering some clever attempts at the brush (all stuffed in the bureau drawer no doubt); or, ‘You presumptuous little toad”— some wretch’s scowl to a woman teeming with potential—take a look: has not her poetry some exquisite quality in it? Something delicate, musical about it? A kind of gossamer sing-song? Yet she is called a “presumptuous toad”—simply for putting pen to paper. Perhaps it is this scowling wretch himself who should be called a “presumptuous toad”—but let’s save this idea for later.

Virginia Woolf argues that the reason woman of the past—before Jane Austen, i.e.—have not produced works of genius is not because they were incapable, but because they were imprisoned. In order for an artist to produce a work of genius, the artist’s mind must be entirely free, entirely at ease. The artist must have the liberty to live and think spaciously. How, then, is one expected to create a great piece of art if one is burdened by the necessity to labor endlessly for material things.

Virginia sums this up towards the end of the essay, saying that “intellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And woman have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time."

How, then, can a woman be expected to create great art when she is repeatedly told, in a very hostile manner, that she is incapable of writing the plays of Shakespeare and the poems of Milton. How can she create when she is denied an education, when her only means to support herself is another man? And then, of course, the children come along. One knows how great an obligation that could be—especially when they come in tens and twelves. (I’m speaking of the past of course.)

But what about the well-to-do woman, you ask… Virginia reminds us that, even if a woman managed to possess money and a room of her own, there was no literary or artistic tradition for her to take off from, save that of men’s of course. But that tradition is not exactly fit for the woman artist—for the shape of her art. Women’s art is—

But wait—if you are interested in these ideas, I urge you to buy a copy of the book. For I shan’t summarize all the points Mrs. Woolf makes. (The winter break is loaded with time. Read it, if you’re interested. It shows an interesting side of Virginia Woolf.)

Yes, Virginia Woolf. How could I spare you a photo?

She has many curious things to say about Austen, Eliot, and the Brontes (Charlotte and Emily) as well. She suggests, for example, that Charlotte Bronte had more genius in her than Jane Austen; yet, Charlotte's resentment at her restricting circumstances filled her with anger, and therefore did not allow her to express her genius clearly and wisely. Jane Austen’s mind, like Shakespeare’s mind, Virginia tells us, was entirely free. It did not resent or hate, and perhaps that is why we know so little about it.

Perhaps what makes A Room of One’s Own so powerful is its suggestiveness. Virginia repeatedly suggests that many great artists have existed and died, unable to express their genius. She even conjures up a picture of a Miss Judith Shakespeare, who, equal to her brother William in talents, is driven to commit suicide by her extreme frustration at her situation. A Room of One’s Own illuminates the tacit difficulties women faced in attempting to write in the past, and urges women of the day (1929) to be bold and create, and of course, to aquire money and a room of their own.

Awaiting the public's reception of A Room of One's Own, Virginia writes in her diary:

“I forecast, then, that I shall get no criticism, except of the evasive jocular kind… that the press will be kind and talk of its charm, & sprightliness; also I shall be attacked for a feminist & and hinted at for a sapphist…I shall get a good many letters from young women. I’m afraid it will not be taken seriously…It is a trifle, I shall say; so it is but I wrote it with ardor and conviction…You feel the creature arching its back and galloping on, though as usual much is watery & flimsy & pitched in too high a voice.”

As the introducer to my paperback copy, Mary Gordon, points out, her standars were mercilessly high: "A trifle? Hardly."

Saturday, December 18, 2010

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Letters

Dear Darren Criss,

I think you should stop making love eyes at Chris Colfer, and start making them at Nicky.

Sincerely,

Nicky

P.S. Hai.

I think you should stop making love eyes at Chris Colfer, and start making them at Nicky.

Sincerely,

Nicky

P.S. Hai.

Monday, December 13, 2010

More Nabokov!

Nabokov, browsing through his Lolita collection:

P.S. As I am exceedingly busy now, writing conference papers for school, I must delay writing reviews for the other Woolf novels I spoke of till early on next week. I will review on a much more regular basis then.

P.S. As I am exceedingly busy now, writing conference papers for school, I must delay writing reviews for the other Woolf novels I spoke of till early on next week. I will review on a much more regular basis then.

Saturday, December 11, 2010

Nabokov interview

Oh my goodness... Nicole, Melissa, listen to this interview.

Friday, December 10, 2010

Misery won't you comfort me in my time of need

Some Rather Whimsical Thoughts on Mrs. Woolf’s To The Lighthouse (1927)

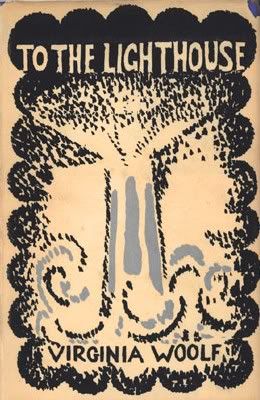

I begin with a picture of the original 1927 edition, with cover art by Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s sister. They were quite the duo, weren't they?

The margins in the latest edition of To the Lighthouse are unusually wide, as if the editor thought it necessary for some reason or other. I can’t help but fancying that they serve as a sort of picture frame for Virginia’s prose—a sort of landscape—blank, spacious, where her prose can ruminate in its own reflections, where it can think freely, without the suffocating clutter of a half-inch girdle. Indeed, I wonder! that once one sets the book down, there is not a kind of profound, under-water brooding buzzing within the closed copy. It was certainly the editor’s intention, in having the margins expanded, to call attention to Virginia’s prose, and perhaps to encourage one to respond, along these margins (with a pencil, of course), to the various impressions the novel gives, and to the questions it prompts.

To the Lighthouse is continually ranked among the finest novels of the twentieth century, and is considered, by some critics, to be 'twentieth-century novel' itself; yet, however critics choose to rank this novel among the masterworks of the twentieth century, To the Lighthouse is generally regarded, by Woolfians, as her masterpiece. But let me explain, for those of you who’ve yet to read this novel.

Consider how momentary, how elusive are the things which influence our thoughts the most. Consider those silent impressions that occur to us throughout the day, that haunt us throughout the night—that curious pinch of intuition that tells one, as one rocks peacefully on the veranda, or glares into the sun, “this is all, this is all.”

For a moment, one understands. But with the flap of a door, of a wave, of a hand it is gone. There is, of course, the other issue of communication, of reaching out for another, of trying to understand another. So we find ourselves, slighted, verging on despair, as the result of a mere glance. “I irritate her,” one suspects, or “she’s somehow compensating for the death of her father.” The most telling things about human nature are these internal suppositions—yet how capricious these are! flitting this way and that, as butterflies do. And as soon as one’s at liberty to examine these bright-winged creatures, perched on their blue-green leaves, off they go! Off! —like flick of a match! But you are probably wondering what all this has to do with Virginia Woolf. When it is said that Mrs. Woolf is one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century, it is said for a reason. For in her novels, Virginia manages to verbalize the various impressions, thoughts, and intuitive sparks that occur to us throughout the day ( this is “stream of consciousness” at its best). “She gives language to the silent space that separates people and the space that they transgress to reach eachother,” proclaims the blurb on the back of my paperback. The complexity and awareness of her prose could have arisen from no one but Virginia herself, whose profound confrontationality (I coin the word) with life, allows her to examine it from an almost objective perspective. So we see, in To the Lighthouse, pages upon pages of butterflies (those capricious sprites of one’s internal life!), pinned down, curiously labled, available to be examined at one’s leisure—no flitting involved. She is, for this reason, the most philosophical of lepidopterists. Ha!

To the Lighthouse has no plot, just as our lives have no plot. It is an internal voyage. Throughout the whole novel, however, there is always a kind of misty energy compelling readers towards the lighthouse—there, right off the shore, with all the wind! and the gulls! and the sea (how it roars!), splashing this way and that.

********************************************

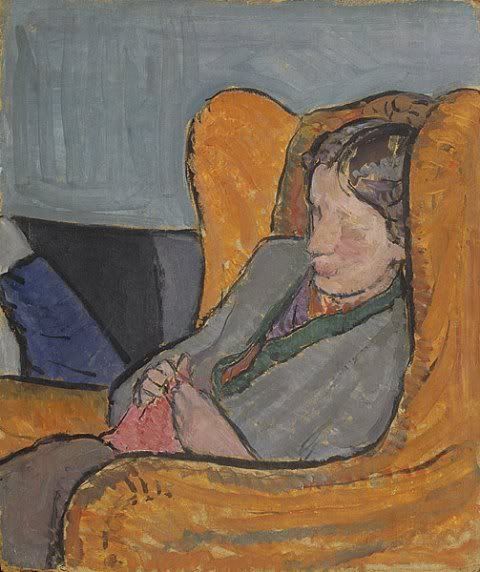

Here's a portrait of Virginia by her sister, Vanessa. Behold.

The fading of Virginia’s countenance is a modernist way of saying, “Dear, how elusive identity is!” For, couched in her banana chair, drifting casually into sleep, Virginia seems to fade out of her very own identity. Her physical features are independent from her internal existence, suggests this painting. “But what has this got to do with To the Lighthouse,” I can hear you saying... Well, very much actually. For it is this modernist compulsion to turn abstractions into tangible forms, to conceptualize the internal life that characterize much of Virginia’s work (specifically, To the Lighthouse, which is a controlled whirlwind of impressions). Virginia consciously made an effort to transcribe this kind of art (she actually refers to this particular portrait in some letter or other) in a literary form. O, those modernists!

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Please excuse my cheesiness to follow.

Why is it that we can throw around the word "love" when it doesn't mean anything, but can't seem to say it at all when it means everything? I love you. There, I've said it and I mean it and it's real. Who cares who says it first? If I feel it, I should tell you and tell you frequently because life is short and unpredictable and I want you to know how much you really mean to me. Now it's out in the world and you know and it's up to you to decide what you want to do with that heavy bit of information. You shouldn't be shocked. I've known I love you for quite a while now. I'm not asking you to say it back or feel obligated to me in some ridiculous cliche manner. I just want you, however you feel about me in return, but I'm pretty sure you love me too. I've seen the way you look at me like I'm so much more than you could have deserved, like I matter too much for you to ever want to hurt me. It's absolutely terrifying to trust you with every inch of my heart, but you're one of my best friends and I love you. I'll say it a thousand times if you want. And no, it's not too soon especially after everything we've been through.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

On Mrs. Dalloway

This is the first in a parade of blogs I plan on writing, in which I’ll review certain novels, essays, and stories by Virginia Woolf. (As I am reading a lot of her works for a university project, I feel as if I must.) This blog is dedicated to Mrs. Dalloway (1925); however, expect to see reviews on To The Lighthouse, Jacob’s Room, Flush: a biography, The Waves, Between the Acts, and A Room of One’s Own in the coming days.

Mrs. Woolf

********************************************

A Tidbit on Mrs. Dalloway:

Despite its taking place in a single day, Mrs. Dalloway is an epic in its own right; for it unravels all the mysteries of time, beauty, and consciousness in the span of a single, sunny June day in 1923.

The day is hot, and all about London is a tingling, a bustling of life—shops and motor cars and omnibuses and airplanes and salmon on ice blocks and plumes on ladies’ hats, going this way and that. Virginia redefines the novel, insisting that the enormous can be found in the simple--can be seen in the goings on of everyday life—in this errand or that. Hush, she seems to say to the Victorians who preceded her; for you are missing the point!

Of Mrs. Dalloway Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours, says it “contains some of the most beautiful, complex, incisive and idiosyncratic sentences ever written in English.” And indeed he is right. Virginia Woolf is perhaps one of the greatest stylists to ever write in the English language. Her approach is in fact very Shakespearean, in that one detects in it the ecstatic desire to use language to its very limit, to the very brim of its potential. Language, as a potential to illuminate, to create, to speak truth is, alas, a sea! And swimming in this infinite pool, flowing here and there, are the words that can teach us, save us, redeem us. (How vast the sea is!) And yet, given this glorious sea, which all writers are!, some choose merely to go water skiing or boating—these are the poor novelists… —But Virginia! She swims leagues below the surface, where there is but darkness—and to bring her findings to the surface, to the light, was her life’s devotion. And so we see, in Mrs. Dalloway, a panoply of her precious findings, moist and shriveled form the pressured depths. But, alas, there they are.

The manner in which she uses grammar is also extraordinary—but I’ll write on this another time, for, if not, this review would become absurdly lengthy.

What’s so extraordinary about this novel, and, indeed, all of Virginia’s work, is the way in which Virginia is able to put the most subtle of human connections into words. Her greatest gift is her recognition, her fleshless sensibilities, which allow her to recognize the workings of the mind in seeming trivialities—the swish of a curtain, the flick of a switch—and legitimize them through description, suggesting just how telling the smallest things are. I’m aware that I’m speaking in abstractions. –Yet it is these abstractions that she miraculously identifies in a smile or a gesture.

Where to? To Piccadilly Street. To the Dalloway home. To Peter Walsh’s mind. To Burton twenty years ago. For that is how this story is told. Virginia jumps from consciousness to consciousness in London, exploring the intricate connection between time and thought. Present blurs into past; past blurs into present. A moment we’re with Mrs. Dalloway, another with Peter Walsh, to whom she considered marrying in the past.

All of life seems to be capsulated in this single day, and Virginia shows us, through her characters’ reflections what happiness really is. It is these flowers—blue, red, lemon—that little girl with the pink dress, that little robin up in the tree, this day, this moment, her smile, his laugh. This is actually one of the largest themes in the novel: the idea that happiness is a moment itself—that life is a moment.

If you are a human being you can relate to Mrs. Dalloway. If you haven’t read any Woolf before, start with this book. There are so many exquisite moments. It’s very much like a treasure box, actually. Her images and phrasing is immaculate.

Proof:

“…for the shock of Lady Bruton asking Richard to lunch without her made the moment in which she stood shiver, as a plant on the river-bed feels the shock of a passing oar and shivers: so she rocked: so she shivered.”

“..There were flowers: delphiniums, sweet peas, bunches of lilac; and carnations, masses of carnations. There were roses; there were irises. And then, opening her eyes, how fresh like frilled linen clean from a laundry laid in wicker trays the roses looked; and dark and prim the red carnations, holding their heads up; and all the sweet peas spreading in their bowls, tinged violet, snow white, pale-as if it were the evening and girls in muslin frocks came out to pick sweet peas and roses after the superb summer's day, with its almost blue-black sky, its delphiniums, its carnations, its arum lilies was over; and it was the moment between six and seven when every flower-roses, carnations, irises, lilac-glows; white, violet, red, deep orange; every flower seems to burn by itself, softly, purely, in the misty beds; and how she loved the grey-white moths spinning in and out, over the cherry pie, over the evening primroses!”

Virginia also makes it a point to spot the things of adventure stories—pirates and skeletons and gold—in daily London life, making a point that life is, indeed, a kind of adventure. And to live only for one day is very dangerous (there is a quote in like this somewhere in the book).

I feel as if I haven’t said anything about this novel. But I have work to do.

Mrs. Woolf

********************************************

A Tidbit on Mrs. Dalloway:

Despite its taking place in a single day, Mrs. Dalloway is an epic in its own right; for it unravels all the mysteries of time, beauty, and consciousness in the span of a single, sunny June day in 1923.

The day is hot, and all about London is a tingling, a bustling of life—shops and motor cars and omnibuses and airplanes and salmon on ice blocks and plumes on ladies’ hats, going this way and that. Virginia redefines the novel, insisting that the enormous can be found in the simple--can be seen in the goings on of everyday life—in this errand or that. Hush, she seems to say to the Victorians who preceded her; for you are missing the point!

Of Mrs. Dalloway Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours, says it “contains some of the most beautiful, complex, incisive and idiosyncratic sentences ever written in English.” And indeed he is right. Virginia Woolf is perhaps one of the greatest stylists to ever write in the English language. Her approach is in fact very Shakespearean, in that one detects in it the ecstatic desire to use language to its very limit, to the very brim of its potential. Language, as a potential to illuminate, to create, to speak truth is, alas, a sea! And swimming in this infinite pool, flowing here and there, are the words that can teach us, save us, redeem us. (How vast the sea is!) And yet, given this glorious sea, which all writers are!, some choose merely to go water skiing or boating—these are the poor novelists… —But Virginia! She swims leagues below the surface, where there is but darkness—and to bring her findings to the surface, to the light, was her life’s devotion. And so we see, in Mrs. Dalloway, a panoply of her precious findings, moist and shriveled form the pressured depths. But, alas, there they are.

The manner in which she uses grammar is also extraordinary—but I’ll write on this another time, for, if not, this review would become absurdly lengthy.

What’s so extraordinary about this novel, and, indeed, all of Virginia’s work, is the way in which Virginia is able to put the most subtle of human connections into words. Her greatest gift is her recognition, her fleshless sensibilities, which allow her to recognize the workings of the mind in seeming trivialities—the swish of a curtain, the flick of a switch—and legitimize them through description, suggesting just how telling the smallest things are. I’m aware that I’m speaking in abstractions. –Yet it is these abstractions that she miraculously identifies in a smile or a gesture.

Where to? To Piccadilly Street. To the Dalloway home. To Peter Walsh’s mind. To Burton twenty years ago. For that is how this story is told. Virginia jumps from consciousness to consciousness in London, exploring the intricate connection between time and thought. Present blurs into past; past blurs into present. A moment we’re with Mrs. Dalloway, another with Peter Walsh, to whom she considered marrying in the past.

All of life seems to be capsulated in this single day, and Virginia shows us, through her characters’ reflections what happiness really is. It is these flowers—blue, red, lemon—that little girl with the pink dress, that little robin up in the tree, this day, this moment, her smile, his laugh. This is actually one of the largest themes in the novel: the idea that happiness is a moment itself—that life is a moment.

If you are a human being you can relate to Mrs. Dalloway. If you haven’t read any Woolf before, start with this book. There are so many exquisite moments. It’s very much like a treasure box, actually. Her images and phrasing is immaculate.

Proof:

“…for the shock of Lady Bruton asking Richard to lunch without her made the moment in which she stood shiver, as a plant on the river-bed feels the shock of a passing oar and shivers: so she rocked: so she shivered.”

“..There were flowers: delphiniums, sweet peas, bunches of lilac; and carnations, masses of carnations. There were roses; there were irises. And then, opening her eyes, how fresh like frilled linen clean from a laundry laid in wicker trays the roses looked; and dark and prim the red carnations, holding their heads up; and all the sweet peas spreading in their bowls, tinged violet, snow white, pale-as if it were the evening and girls in muslin frocks came out to pick sweet peas and roses after the superb summer's day, with its almost blue-black sky, its delphiniums, its carnations, its arum lilies was over; and it was the moment between six and seven when every flower-roses, carnations, irises, lilac-glows; white, violet, red, deep orange; every flower seems to burn by itself, softly, purely, in the misty beds; and how she loved the grey-white moths spinning in and out, over the cherry pie, over the evening primroses!”

Virginia also makes it a point to spot the things of adventure stories—pirates and skeletons and gold—in daily London life, making a point that life is, indeed, a kind of adventure. And to live only for one day is very dangerous (there is a quote in like this somewhere in the book).

I feel as if I haven’t said anything about this novel. But I have work to do.

Friday, December 3, 2010

On This Open Road

What's life without passing a few speed bumps? As long as we're in the same car, on the same journey, things will work out. The destination is hardly as important as the ride, and as long as we take it slow on this open road, we'll make it there alright.

some awesome vedios

Strawberry Swing music vedio

Angela in S.T.!!

Virginia Woolf's voice!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! O, Virginia!

Angela in S.T.!!

Virginia Woolf's voice!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! O, Virginia!

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Dinner at Mrs. Lawrence’s Mansion

It just so happens that for the past three years or so the president of my college—a dry, smiling woman, with a predilection for Joyce—has adopted a new tradition of hosting small dinners, for the first years, at her mansion. An enormous estate reining over the avenue of Kimball, whose key has shifted through the years through the hands of ten college presidents at least.

But where shall I begin? O, yes! with the moon. For there it was, brightening the black sky, like a lantern in a dungeon. One makes his way across the lawn, embowered by the oaks’ shady limbs, and eventually reaches the door. It stands firm and exclusive in a little cavern of cobble stones. May I take your coat, a woman asks. Coats are quite necessary in these frigid places, and so this question is asked, I suppose, more often up north. This is not Miami, to be sure! Mrs. Lawrence awaits you in the living room, the woman says…

The room was bright and spacious. On the oak-paneled walls, one may spy troll-like men, hunched above pilasters or columns, lugging wood on their backs—one’s eyes wander and meet the sight of a fairy-maiden dancing in a garden. There were many curious carvings in the paneling, and one got the feeling that the walls were alive, teeming with tales that unfolded in the dark, when the room was left alone. And as the room began to fill with the jitter of the guests, one knew that the walls, and their goblin creatures were heeding to it all. There were tapestries and books and paintings—a Steinway in the corner, and a massive alcove with nothing but a rosy-amber vase, exquisitely shaped, and set on a wooden table. How nice it must be to sit in the chair and watch the afternoon sun stream through the French windows—through the splendid vase, casting rosy-amber lights about the room.

But there was something silly about the whole thing. There were about a dozen of us, sitting around a small chest in the center of the room, topped with a platter of vegetables and a bowl of dip. You could have sworn it had all been filched from the pages of some fancy home-living magazine. And how could one not laugh, when one looked on the tomatoes and the celery and the cauliflower stalks?

A vegetable is not funny in itself, when its purpose is to feed—to provide nutritional sustenance, to give one some reason for healthy complacency. But when vegetables are set out to impress, to display--to boast of their perfection, they consequently appear absurd. And the same stalk of cauliflower that appeases the vanity of the hostess provokes another into a giggle, and stimulates a third into a philosophical reverie.

Dinner followed in the dining room, in which, the president has informed me, numerous dinner-parties have been thrown over the past hundred years. The food is delicious; it is from the East, where the air is full of spices. All my companions feel it the perfect time to make complaints about disagreeable things that happen on campus, and though the president smiles (a hospitality class told her she must!), she is tired behind her mirthful mask. My romantic mind tells me she wants to peruse through Woolf's diaries (She's a scholar on modernism)--but she really just wants to lay down with her husband, Peter. Peter? Was that his name?

It was wonderful, I say, just before I leave. Though it was actually rather silly, if you really think about it.

But where shall I begin? O, yes! with the moon. For there it was, brightening the black sky, like a lantern in a dungeon. One makes his way across the lawn, embowered by the oaks’ shady limbs, and eventually reaches the door. It stands firm and exclusive in a little cavern of cobble stones. May I take your coat, a woman asks. Coats are quite necessary in these frigid places, and so this question is asked, I suppose, more often up north. This is not Miami, to be sure! Mrs. Lawrence awaits you in the living room, the woman says…

The room was bright and spacious. On the oak-paneled walls, one may spy troll-like men, hunched above pilasters or columns, lugging wood on their backs—one’s eyes wander and meet the sight of a fairy-maiden dancing in a garden. There were many curious carvings in the paneling, and one got the feeling that the walls were alive, teeming with tales that unfolded in the dark, when the room was left alone. And as the room began to fill with the jitter of the guests, one knew that the walls, and their goblin creatures were heeding to it all. There were tapestries and books and paintings—a Steinway in the corner, and a massive alcove with nothing but a rosy-amber vase, exquisitely shaped, and set on a wooden table. How nice it must be to sit in the chair and watch the afternoon sun stream through the French windows—through the splendid vase, casting rosy-amber lights about the room.

But there was something silly about the whole thing. There were about a dozen of us, sitting around a small chest in the center of the room, topped with a platter of vegetables and a bowl of dip. You could have sworn it had all been filched from the pages of some fancy home-living magazine. And how could one not laugh, when one looked on the tomatoes and the celery and the cauliflower stalks?

A vegetable is not funny in itself, when its purpose is to feed—to provide nutritional sustenance, to give one some reason for healthy complacency. But when vegetables are set out to impress, to display--to boast of their perfection, they consequently appear absurd. And the same stalk of cauliflower that appeases the vanity of the hostess provokes another into a giggle, and stimulates a third into a philosophical reverie.

Dinner followed in the dining room, in which, the president has informed me, numerous dinner-parties have been thrown over the past hundred years. The food is delicious; it is from the East, where the air is full of spices. All my companions feel it the perfect time to make complaints about disagreeable things that happen on campus, and though the president smiles (a hospitality class told her she must!), she is tired behind her mirthful mask. My romantic mind tells me she wants to peruse through Woolf's diaries (She's a scholar on modernism)--but she really just wants to lay down with her husband, Peter. Peter? Was that his name?

It was wonderful, I say, just before I leave. Though it was actually rather silly, if you really think about it.

Monday, November 29, 2010

conversations in my brain?

......"See I'm paranoid, but in this weird way."

"I don't get it."

"It's just off, you know. Like last week I was taking my dog for a walk, well it's not really my dog. It's my brothers, but he's in school. Anyway this girl backed into my neighbor's driveway, and she didn't look like she would do anything incriminating or anything like that. Anyway, as I was walking my brother's dog closer to the car I just imagined me walking past it and her pulling out a gun and shooting me, so I crossed the street, just to avoid walking directly in front of it."

"Well did she have the windows down?"

"What?"

"Did she have the windows down? If she wanted to shoot you she'd probably need the windows down, unless she's want to shoot you through her window."

"Well yeah I guess that's true. But isn't it weird, the way that I'm paranoid?"

"Not really. It just sounds like your normal paranoid."

"Well that wasn't really a good example. I'm bad at explaining things. Like sometimes when I'm falling asleep in my room, you know how my room is secluded and I can't really hear anything because the heater gets to be so loud, and all?"

"Yeah."

"Well sometimes I imagine that the zombie apocalypse is just starting and there's a zombie in my house, and it's already infected my parents. So I freak out and go make sure all the doors are locked."

"Yeah, it sounds like you're just normal paranoid."

"I guess so."

"I don't get it."

"It's just off, you know. Like last week I was taking my dog for a walk, well it's not really my dog. It's my brothers, but he's in school. Anyway this girl backed into my neighbor's driveway, and she didn't look like she would do anything incriminating or anything like that. Anyway, as I was walking my brother's dog closer to the car I just imagined me walking past it and her pulling out a gun and shooting me, so I crossed the street, just to avoid walking directly in front of it."

"Well did she have the windows down?"

"What?"

"Did she have the windows down? If she wanted to shoot you she'd probably need the windows down, unless she's want to shoot you through her window."

"Well yeah I guess that's true. But isn't it weird, the way that I'm paranoid?"

"Not really. It just sounds like your normal paranoid."

"Well that wasn't really a good example. I'm bad at explaining things. Like sometimes when I'm falling asleep in my room, you know how my room is secluded and I can't really hear anything because the heater gets to be so loud, and all?"

"Yeah."

"Well sometimes I imagine that the zombie apocalypse is just starting and there's a zombie in my house, and it's already infected my parents. So I freak out and go make sure all the doors are locked."

"Yeah, it sounds like you're just normal paranoid."

"I guess so."

MORE PICAS AND JAMZ..... and this was supposed to be a literary blog. Oh well!

Labels:

Josh Beech,

Louis Garrell,

Nicky,

Passion,

So jokes,

The Like,

Uncle Karl

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Manger

...This song describes my life right now. Also....

...this song.

All of a sudden everything is making sense and no sense all at the same time. Which shouldn't be right, but maybe it is right. I don't know! Jesus, life is confusing. You think it's all good, and then BOOM, it's not. And you're like "For fucks sake." Jeez, little world, I don't know what I'll do next. I think I'll just stick around here fester and grow some mold or something, buy a French Bulldog, name it Louis the Frenchman and call it a day. Plan.

Also I want to be Tennessee Thomas

Or maybe I'll just be Nicky. I haven't decided yet.

P.S. (whoever told me that Angus and Julia Stone was my type of music is a rotten dirty liar. They're good and all, but they're just too much for me)

Labels:

confusion,

jams,

Led Zeppelin,

life,

Nicky,

Tennessee Thomas,

The Like,

Wavves

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Rambling about Women's Expressions

An unusual observation—for a man at least:

Statistics prove that, on average, women are more intelligent than men.

Ladies, your blushes are merited!

Now, for my unusual observation…it is unusual strictly because it is being made by a male—i.e., me.

Rarely is one struck by a man’s having an “intelligent” expression… I’m just testing the waters here, so don’t jump on me! But do think. How often does one see a man and think to one’s self, “My, what intelligent eyes!”?

Seldom… is my argument. Yet I have often encountered women and thought, “What intelligent eyes!”

There is something quicker, sharper, more incisive about the feminine physiognomy. A masculine expression can be intolerably blunt in a way a femenine one can never be.

O, feminine sagacity!

Statistics prove that, on average, women are more intelligent than men.

Ladies, your blushes are merited!

Now, for my unusual observation…it is unusual strictly because it is being made by a male—i.e., me.

Rarely is one struck by a man’s having an “intelligent” expression… I’m just testing the waters here, so don’t jump on me! But do think. How often does one see a man and think to one’s self, “My, what intelligent eyes!”?

Seldom… is my argument. Yet I have often encountered women and thought, “What intelligent eyes!”

There is something quicker, sharper, more incisive about the feminine physiognomy. A masculine expression can be intolerably blunt in a way a femenine one can never be.

O, feminine sagacity!

Monday, November 22, 2010

The Lady of Shalott (1842)

Here is a lovely animation for one of my favorite poems, Tenneyson's The Lady of Shalott. Enjoy!

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro' the field the road runs by

To many-tower'd Camelot;

And up and down the people go,

Gazing where the lilies blow

Round an island there below,

The island of Shalott.

Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Through the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four grey walls, and four grey towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

By the margin, willow veil'd,

Slide the heavy barges trail'd

By slow horses; and unhail'd

The shallop flitteth silken-sail'd

Skimming down to Camelot:

But who hath seen her wave her hand?

Or at the casement seen her stand?

Or is she known in all the land,

The Lady of Shalott?

Only reapers, reaping early,

In among the bearded barley

Hear a song that echoes cheerly

From the river winding clearly;

Down to tower'd Camelot;

And by the moon the reaper weary,

Piling sheaves in uplands airy,

Listening, whispers, " 'Tis the fairy

Lady of Shalott."

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving through a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot;

There the river eddy whirls,

And there the surly village churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd lad,

Or long-hair'd page in crimson clad

Goes by to tower'd Camelot;

And sometimes through the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two.

She hath no loyal Knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror's magic sights,

For often through the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot;

Or when the Moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed.

"I am half sick of shadows," said

The Lady of Shalott.

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro' the leaves,

And flamed upon the brazen greaves

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A red-cross knight for ever kneel'd

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glitter'd free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle bells rang merrily

As he rode down to Camelot:

And from his blazon'd baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armor rung

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell'd shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn'd like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

As often thro' the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, burning bright,

Moves over still Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow'd;

On burnish'd hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow'd

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flashed into the crystal mirror,

"Tirra lirra," by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces through the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

"The curse is come upon me," cried

The Lady of Shalott.

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining.

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Down she came and found a boat

Beneath a willow left afloat,

And around about the prow she wrote

The Lady of Shalott.

And down the river's dim expanse

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance --

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

Lying, robed in snowy white

That loosely flew to left and right --

The leaves upon her falling light --

Thro' the noises of the night,

She floated down to Camelot:

And as the boat-head wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her singing her last song,

The Lady of Shalott.

Heard a carol, mournful, holy,

Chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her blood was frozen slowly,

And her eyes were darkened wholly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot.

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden-wall and gallery,

A gleaming shape she floated by,

Dead-pale between the houses high,

Silent into Camelot.

Out upon the wharfs they came,

Knight and Burgher, Lord and Dame,

And around the prow they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Who is this? And what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they crossed themselves for fear,

All the Knights at Camelot;

But Lancelot mused a little space

He said, "She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott."

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro' the field the road runs by

To many-tower'd Camelot;

And up and down the people go,

Gazing where the lilies blow

Round an island there below,

The island of Shalott.

Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Through the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four grey walls, and four grey towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

By the margin, willow veil'd,

Slide the heavy barges trail'd

By slow horses; and unhail'd

The shallop flitteth silken-sail'd

Skimming down to Camelot:

But who hath seen her wave her hand?

Or at the casement seen her stand?

Or is she known in all the land,

The Lady of Shalott?

Only reapers, reaping early,

In among the bearded barley

Hear a song that echoes cheerly

From the river winding clearly;

Down to tower'd Camelot;

And by the moon the reaper weary,

Piling sheaves in uplands airy,

Listening, whispers, " 'Tis the fairy

Lady of Shalott."

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving through a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot;

There the river eddy whirls,

And there the surly village churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd lad,

Or long-hair'd page in crimson clad

Goes by to tower'd Camelot;

And sometimes through the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two.

She hath no loyal Knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror's magic sights,

For often through the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot;

Or when the Moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed.

"I am half sick of shadows," said

The Lady of Shalott.

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro' the leaves,

And flamed upon the brazen greaves

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A red-cross knight for ever kneel'd

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glitter'd free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle bells rang merrily

As he rode down to Camelot:

And from his blazon'd baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armor rung

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell'd shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn'd like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

As often thro' the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, burning bright,

Moves over still Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow'd;

On burnish'd hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow'd

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flashed into the crystal mirror,

"Tirra lirra," by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces through the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

"The curse is come upon me," cried

The Lady of Shalott.

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining.

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Down she came and found a boat

Beneath a willow left afloat,

And around about the prow she wrote

The Lady of Shalott.

And down the river's dim expanse

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance --

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

Lying, robed in snowy white

That loosely flew to left and right --

The leaves upon her falling light --

Thro' the noises of the night,

She floated down to Camelot:

And as the boat-head wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her singing her last song,

The Lady of Shalott.

Heard a carol, mournful, holy,

Chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her blood was frozen slowly,

And her eyes were darkened wholly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot.

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden-wall and gallery,

A gleaming shape she floated by,

Dead-pale between the houses high,

Silent into Camelot.

Out upon the wharfs they came,

Knight and Burgher, Lord and Dame,

And around the prow they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Who is this? And what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they crossed themselves for fear,

All the Knights at Camelot;

But Lancelot mused a little space

He said, "She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott."

Imagining Sleep

Imagine you're on an island, lying on the beach.

It's just you and me under the biggest palm tree.

We have services that are only the finest.

The sun is just lightly kissing our freckled brown skin.

We're relaxing on the fresh powdery sand.

Resting by the shore.

Hearing the waves coming and going, coming and going.

The sound of them crashing matches our steady breathing.

Finally, we sleep.

It's just you and me under the biggest palm tree.

We have services that are only the finest.

The sun is just lightly kissing our freckled brown skin.

We're relaxing on the fresh powdery sand.

Resting by the shore.

Hearing the waves coming and going, coming and going.

The sound of them crashing matches our steady breathing.

Finally, we sleep.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

E. H. Gombrich: Stories of History and Art

This is a very special blog, dedicated to Austrian art historian E. H. Gombrich. If this name is unfamiliar to you, don’t feel bad; it was only until very recently, while browsing through certain amazon book reviews, that I happened upon his name.

The man himself, people:

Free Music

Gombrich is internationally acclaimed for his revolutionary approach to writing about history and art. I’m currently making my way through his two most famous books, A Little History of the World and The Story of Art—and what a pleasant way that is! Both books are designed to serve as introductions to the exciting fields of world history and art history; however, unlike many historians, whose ‘introductions’ to these worlds bombard one with an endless array of fancy terms and lofty descriptions, Gombrich's main aim, in these two volumes, is to make the seemingly esoteric world of art history accessible to all. Art is for everyone, Gombrich seems to say, as he gazes below at the mass of pomp and pretension that has become synonymous with art-writing today. Let me, however, not speak of both books as if their respective aims were identical.

A Little History of the World (1935) is geared toward pre-teen readers, however there is much to be gained from it by readers of all ages.

“All stories begin with ‘once upon a time,’” Gombrich begins, “and that’s just what this story is all about: what happened, once upon a time.”

I urge you to get a copy of this book. It’s remarkably entertaining, and reminds one just how fascinating history can be (none of that academic pomp included). Beginning with the geological beginnings of our planet, Gombrich leads us through the ancient civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Babylonia all the way to the creation of the atomic bomb. (I’m by Alexander the Great now.) He makes history fun, while still managing to teach you many curious things along the way… and I’m not the only one who thinks so. This book has been translated into dozens of languages and has remained an international best-seller for quite some time now. (It briefly fell out of publication during WW2, when Nazi’s thought its tone and conclusion too pacifistic—go figure)

(Nicky, you’ll love this book! I know your keen on history.)

I just started The Story of Art this afternoon, so I don’t have as much to say, but just from reading his introduction “On Art and Artists,” one can tell one’s in for a treat!

In condemning the snobbery often encountered in the ‘world of fine Art’—note the capital ‘A’—Gombrich writes:

“It is infinitely better not to know anything about art than to have the kind of half-knowledge which makes for snobbishness.”

It’s a quick read for a 650-page art history book. But I’m telling you, he’s wonderfully entertaining, very knowledgeable, and a born teacher. This is the MOST HIGHLY REGARDED introduction to art history in THE WORLD. And it has loads of great pictures—as all art history books should!

MySpace Codes

If you’re interested in art history, but have found more academically ambitious volumes a bit daunting at times (because of the sheer profusion of obscure terms and names), this is a great place to dive into the strange and marvelous world of art. --I'm just beginning to do so, and I can assure you that the water's warm and splendid.

The man himself, people:

Free Music

Gombrich is internationally acclaimed for his revolutionary approach to writing about history and art. I’m currently making my way through his two most famous books, A Little History of the World and The Story of Art—and what a pleasant way that is! Both books are designed to serve as introductions to the exciting fields of world history and art history; however, unlike many historians, whose ‘introductions’ to these worlds bombard one with an endless array of fancy terms and lofty descriptions, Gombrich's main aim, in these two volumes, is to make the seemingly esoteric world of art history accessible to all. Art is for everyone, Gombrich seems to say, as he gazes below at the mass of pomp and pretension that has become synonymous with art-writing today. Let me, however, not speak of both books as if their respective aims were identical.

A Little History of the World (1935) is geared toward pre-teen readers, however there is much to be gained from it by readers of all ages.

“All stories begin with ‘once upon a time,’” Gombrich begins, “and that’s just what this story is all about: what happened, once upon a time.”

I urge you to get a copy of this book. It’s remarkably entertaining, and reminds one just how fascinating history can be (none of that academic pomp included). Beginning with the geological beginnings of our planet, Gombrich leads us through the ancient civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Babylonia all the way to the creation of the atomic bomb. (I’m by Alexander the Great now.) He makes history fun, while still managing to teach you many curious things along the way… and I’m not the only one who thinks so. This book has been translated into dozens of languages and has remained an international best-seller for quite some time now. (It briefly fell out of publication during WW2, when Nazi’s thought its tone and conclusion too pacifistic—go figure)

(Nicky, you’ll love this book! I know your keen on history.)

I just started The Story of Art this afternoon, so I don’t have as much to say, but just from reading his introduction “On Art and Artists,” one can tell one’s in for a treat!

In condemning the snobbery often encountered in the ‘world of fine Art’—note the capital ‘A’—Gombrich writes:

“It is infinitely better not to know anything about art than to have the kind of half-knowledge which makes for snobbishness.”

It’s a quick read for a 650-page art history book. But I’m telling you, he’s wonderfully entertaining, very knowledgeable, and a born teacher. This is the MOST HIGHLY REGARDED introduction to art history in THE WORLD. And it has loads of great pictures—as all art history books should!

MySpace Codes

If you’re interested in art history, but have found more academically ambitious volumes a bit daunting at times (because of the sheer profusion of obscure terms and names), this is a great place to dive into the strange and marvelous world of art. --I'm just beginning to do so, and I can assure you that the water's warm and splendid.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

The Best Medicine

Some say laughter is the best medicine; I say crying is. Perhaps because it serves to cure a stronger ailment. Childish, wholehearted crying gives plenty of opportunities to release all the bad in your life. If you're still plagued by something, you're probably not done crying about it. The flood of snot and salt water is enough to cure almost any ill feeling be it sadness, anger, frustration, or well, anything really. It is the ultimate release of emotions and sometimes that is necessary to make you feel better. Don't ever let anyone tell you that crying won't fix anything, because while it can't remove the cause, it clears the mind for a new and inspired course of action. Sometimes, even laughter results in tears, because when the world becomes too much, there's nothing better than letting go for a while.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

A Criticism on Critical Social Behavior

The only person who has to live with you for the rest of your life is you. Make sure you behave like and become someone that anyone would be privileged to spend time with or you really will wind up alone. It's a harsh reality to accept, but sooner or later, it'll hit you whether or not the realization is by choice. Choose your words wisely because all the criticism you ream down upon others appears as only a reflection of your own sense of worthlessness and while it might hurt your intended target at first, it will ultimately be your demise. I refuse to contribute to your destructive behavior, because while you might hurt me now, you'll only wind up running into yourself and that's all you'll have left. So go ahead, be bitter. I wash my hands of all responsibility after this. You received fair warning and you are responsible for your own actions.

Sorry Guys

Uh that last post was made out of confusion and anger. Forgive the cheesiness.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Yes, I am that single friend, deal.

Everyone around me has decided to pair. Yes, pair. All of a sudden my best friend has become, has become best friends +1. Everywhere I go I see couples, I even meet people in couples (true story). I walk to market, couples. Go to the mall, couples. Watch TV, couples. Read a book, couples. Couples, couples, couples, couples. Instead of the Zombie apocalypse, I bring you the couples apocalypse, no single friend is spared. See, I really don't think I'd survive a zombie apocalypse, a couples apocalypse on the other hand, would be an entirely different story. Listening to 10000000000000 plus girls discussing their man problems? I can handle it. Reading 8937462876481664347 love statuses on facebook? Bring it on. 109293874738014892884972958279827492849247297491749164 jealous boyfriends? Easy. 1897398174265826419730`82938928983888845995995999999999999999999999 couples discussing their sex lives? Keep it in the bedroom people. I've got this single friend thing down to a science, that it's almost depressing.

You know, one would think that the last thing two single friends would want to discuss is couples, but it seems that every single person I meet feels the need to tell me about their last relationship. Not that there's anything wrong with that, it's just pretty obnoxious, is all. And by pretty obnoxious I mean really obnoxious. That's really great that your ex girlfriend had a shirt the same color as the one that that girl who just walked by had on, and oh no, it's fine, keep on talking about your ex, pretend I'm not even here, just keep going on talking about him, it's not like you've told me this story five times before.

You want to know what's even worse than all this?! When you feel the need to be in a couple because everyone seems to think it's the bee's knees or something. Bleh. It's the worst feeling in the world. Well maybe not the worst, knowing something horribly fateful might be worse, but it's definitely a close second.

You want to know what I say regarding all this? Fuck it. The bee's knees, the pairing up, all of it. I'm young and free and limitless. I may not be happy all the time, but I'm working on it. So to all my fellow single friends who feel the same way I do, give a nice fuck you to the bee's knees and try to find happiness in your own world, then maybe we can avoid the whole couples apocalypse. Just saying.

You know, one would think that the last thing two single friends would want to discuss is couples, but it seems that every single person I meet feels the need to tell me about their last relationship. Not that there's anything wrong with that, it's just pretty obnoxious, is all. And by pretty obnoxious I mean really obnoxious. That's really great that your ex girlfriend had a shirt the same color as the one that that girl who just walked by had on, and oh no, it's fine, keep on talking about your ex, pretend I'm not even here, just keep going on talking about him, it's not like you've told me this story five times before.

You want to know what's even worse than all this?! When you feel the need to be in a couple because everyone seems to think it's the bee's knees or something. Bleh. It's the worst feeling in the world. Well maybe not the worst, knowing something horribly fateful might be worse, but it's definitely a close second.

You want to know what I say regarding all this? Fuck it. The bee's knees, the pairing up, all of it. I'm young and free and limitless. I may not be happy all the time, but I'm working on it. So to all my fellow single friends who feel the same way I do, give a nice fuck you to the bee's knees and try to find happiness in your own world, then maybe we can avoid the whole couples apocalypse. Just saying.

Embracing the Rain

When I was younger I used to think that rain was God crying down from heaven. It used to make me sad thinking that humans were so disappointing that God could only cry about creating such indecency, but now I like to think of it as His way of washing away the world's sadness to help happiness grow among us. If you really look at the way people act toward each other when they think no one is watching, you might be surprised to find compassion and genuine acts of love are far more ample than violence, hatred, or despair. Though gloomy weather calls for a gloomy demeanor, you can usually expect a rainbow afterward. I like to call that hope.

Amazing Things

I want to see something amazing every single day for the rest of my life.

On Sleeping

What a mystery—to slip in and out of consciousness, as into some warm, narcotic robe. One lays on the bed, thinking this and that: that absurd laugh, those silly little phrases, this bright and lustrous dream. And somewhere along it all dissolves into little drops of light: a lunch pail on the table, a picture of your mother, pretty leaves on trees, in books, on the ground, in the garden. It all dissolves till one is but the solvent itself, overtaken and mute, sinking down, down to the bottom of some deep sea.

*

*

*

*

One rises and raises the blinds—the blinds of one’s eyes, the blinds of the windows. And everything is sunny and strange. Dust floats in the sunny bath, here and there as the thoughts begin to drift again. How queer! One could have sworn he had risen from the grave, for that is how it would feel. But all's just a clever trick—one's organs are ticking still. And the dream is recreated like a phoenix from the ash.

Here's to you Mr. Hemingway

I have been sufficiently obsessed with the likes of Ernest Hemingway as of late. Reading only the first chapters of The Garden of Eden, his word choice and creativity compel me to attempt the same. I would like to take this time to appreciate his genius. He is brilliant and adventurous and sexual in all the best contexts. Enjoy the photos that follow.

Monday, November 15, 2010

A Hiaku to Oscar Wilde

Just came back from Oscar Wilde night at the Tea House!! One of the activities was to write a hiaku to Oscar. Here's mine:

Lemon pedaled sprite,

Cheer us with your dandy phrase;

Rid us of our frowns.

MySpace Codes

You're marvelous, Oscar!!

Lemon pedaled sprite,

Cheer us with your dandy phrase;

Rid us of our frowns.

MySpace Codes

You're marvelous, Oscar!!

A Mind Adrift

My mind has been quite adrift lately. So much has happened- some things I'll never tell. Life is too short and complicated. That's a fact. I wish I could just tear it all out of my brain and throw it on the table; throw away what doesn't matter, the trivial things. I'd keep you though. Everything is a mess- your life, my life, but together, we make sense. I get goosebumps thinking about what we've been through already. Deep breaths and somehow the world makes sense. We know pain, but we know love too. Grandpa loved me and Dad loved you. I hate that we've lost them and I don't know what to say- I've run out of condolences and you've run out of time and I'm sorry that I don't make sense and tend to look the other way, but I'm here for the best and the worst and I'll take it all as my own. I'll take everything you've got, but you have to give too. Give me the very darkest parts of you. I've been there before- I'll know what to do.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

I miss my piano very much—especially all those long, lazy hours of sight-reading... can't wait for Thanksgiving break.

***

Here is the trailer for one of my favorite novels/films, Picnic at Hanging Rock (Joan Lindsey’s classic Australian novel):

It's incredible.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Saturday, November 13, 2010

Writing is Hard

And by hard, I mean impossible, almost that is.

Anyway I'm finding it almost impossible to actually sit down and try to write something substantial for this blog. I mean really write something, something that I won't make me want to throw up after reading. So for now I'll leave the blogging world with the complete opposite of writing until there's some connection between my brain, fingers and the keyboard of my macbook. Enjoy.

Also I love that you're leaving me messages on our blog, Danny=)

Melissa, where dah fuh you at?

Anyway I'm finding it almost impossible to actually sit down and try to write something substantial for this blog. I mean really write something, something that I won't make me want to throw up after reading. So for now I'll leave the blogging world with the complete opposite of writing until there's some connection between my brain, fingers and the keyboard of my macbook. Enjoy.

Also I love that you're leaving me messages on our blog, Danny=)

Melissa, where dah fuh you at?

Activity is a marvelous thing. How I dislike idleness! Yet, after an entire day of mental exertion, my strength is beginning to wane. Therefore I shall not bother to write much—just to announce that everyone should go see Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life… this instant! It’s absolutely hilarious.

Ah! And a 5-7 page psychology paper looms in the distance.

My stomach is making peculiar sounds. Off to dinner.

Friday, November 12, 2010

Some Notes on a Certain Book; Excitement for a Year at Oxford

My mother isn’t exactly a keen reader. She isn’t the kind of person who’d start a book club anyway. So it was with great surprise that I received the information of her decision to host one. My mom being an elementary school teacher, all club members are elementary school teachers as well. Except myself that is! Yes, I decided to join! In such cases it is only right to give support!

At the moment the club is rather disorganized (meeting days have yet to be established) so it is on my own accord that I have begun the club’s first reading selection, The Painted Veil. Yes, The Painted Veil. What a curious title! I’ve only just started it, but it’s already managed to make its own quaint, shocking impression. Indeed: an affair! No, no, no. But what really grabs me is his prose, W. Somerset Maugham’s, that is. (By the way, he was one of Brittan’s most highly regarded, highly paid authors of the 1930s. He was fabulously prolific, writing scores and scores of novels, short stories, plays, travel writings, and literary criticism!!)

Here is a picture of Mr. Somerset himself, taken in 1934:

How could anyone resist running to the bookstore and purchasing one of his books, after having seen this photo? Behold. Something about his prim attire; somewhat grim, bemused countenance; and slicked hair—all white and grey and silvery!—screams literary merit—indeed, screams literary genius!

However, it is not the genius of Shakespeare or Woolf or Nabokov that he possesses. It is an entirely new genius. (I am only a couple of dozen pages in, but let me make some observations!) His prose is remarkably concise for all of the insight/information it carries. What’s more, it is beautifully expressed—unlike someone—cough, cough: Hemingway—cough, cough. Let us not compare this Brit to that American, however…even though they were writing in the same time period!

Here is a trio of noteworthy excerpts:

“His daughters had never looked upon him as anything but a source of income; it had always seemed perfectly natural that he should lead a dog’s life in order to provide them with board and lodging, clothes, holidays and money for odds and ends; and now, understanding that through his fault money was less plentiful, the indifference they had felt for him was tinged with an exasperated contempt.”

“She had a hard and facile fund of chit-chat which in the society she moved in passed for conversation.”

Lastly, the “shrewd” mother Mrs. Grastin’s take on her daughter’s beauty:

“Her beauty depended much on her youth, and Mrs. Garstin realized that she must marry in the first flush of maidenhood.”

[she is trying to make a brilliant marriage for her daughter.]

Anyway, enough about the book! I will write more as I read.

***

On a more scholarly note, I am growing wonderfully impatient for my junior year abroad at Oxford. O, Nicky! I haven’t told you yet, but my school has a one-year study abroad program at Oxford, and I’m planning to do it my junior year. It’s our most competitive study abroad program, but I’m absolutely determined! What an exciting prospect! But everything in its own time, I suppose. I’ll tell you more, Nicole, later, but I have some work to do, so I better conclude for today.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Well! It is only right that thanks is given where it is due. So to you, Nicky, do I offer my warmest thanks! Great job with the page setup—especially the background. The black & white eyes resemble A. Hepburn’s eyes very much, don’t you think? Parisian avenues and pairs of B&W eyes. Very interesting, Nicole. And hi, Mellissa. Two l’s and s’s, right?

This should be a very fun venture!

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)