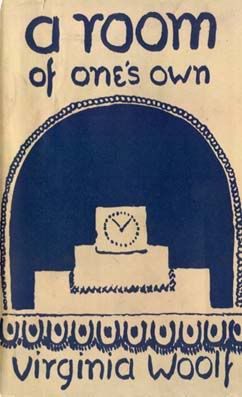

This is the first edition copy of A Room of One’s Own, published by the Hogarth Press. Another lovely cover by Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell. For those of you unfamiliar with the Hogarth Press, it was a small printing press founded in 1917 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf. One could imagine how convenient the press proved in allowing Virginia to publish small sketches and essays here and there—such as this one for instance.

A Room of One’s Own has become vastly popular since its original publication in 1929. The penguin group has recently even decided to fabricate mugs and beach towels, decorated with their own grape-colored edition of Virginia’s essay. For, although over a hundred pages, A Room of One’s Own is characteristically an essay. Here’s Virginia again, innovating literary forms, saying, ‘it can be done, it should be done.’

Yet this bold little book didn’t exactly begin as an essay. It was put together, so I read, “from two papers read to the Arts Society at Newnham and the Odtaa at Girton” (two women's colleges at Cambridge University in 1929).

“A woman,” Mrs. Woolf writes, “must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” This is her essay’s central argument. But how did Mrs. Woolf come to arrive at such a conclusion? What’s all this about women and fiction and rooms?

A Room of One’s Own scrutinizes the limited roles women have been condemned to inhabit in patriarchal societies, and the effects that these limitations have had on them and their art—namely, the art of writing. Throughout history women artists have had to contend with extraordinary amounts of opposition—indeed hostility—to pursue their art. One recalls the stories: ‘It is not your place to produce art,’ said a certain Elizabethan gentleman to his lady, upon discovering some clever attempts at the brush (all stuffed in the bureau drawer no doubt); or, ‘You presumptuous little toad”— some wretch’s scowl to a woman teeming with potential—take a look: has not her poetry some exquisite quality in it? Something delicate, musical about it? A kind of gossamer sing-song? Yet she is called a “presumptuous toad”—simply for putting pen to paper. Perhaps it is this scowling wretch himself who should be called a “presumptuous toad”—but let’s save this idea for later.

Virginia Woolf argues that the reason woman of the past—before Jane Austen, i.e.—have not produced works of genius is not because they were incapable, but because they were imprisoned. In order for an artist to produce a work of genius, the artist’s mind must be entirely free, entirely at ease. The artist must have the liberty to live and think spaciously. How, then, is one expected to create a great piece of art if one is burdened by the necessity to labor endlessly for material things.

Virginia sums this up towards the end of the essay, saying that “intellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And woman have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time."

How, then, can a woman be expected to create great art when she is repeatedly told, in a very hostile manner, that she is incapable of writing the plays of Shakespeare and the poems of Milton. How can she create when she is denied an education, when her only means to support herself is another man? And then, of course, the children come along. One knows how great an obligation that could be—especially when they come in tens and twelves. (I’m speaking of the past of course.)

But what about the well-to-do woman, you ask… Virginia reminds us that, even if a woman managed to possess money and a room of her own, there was no literary or artistic tradition for her to take off from, save that of men’s of course. But that tradition is not exactly fit for the woman artist—for the shape of her art. Women’s art is—

But wait—if you are interested in these ideas, I urge you to buy a copy of the book. For I shan’t summarize all the points Mrs. Woolf makes. (The winter break is loaded with time. Read it, if you’re interested. It shows an interesting side of Virginia Woolf.)

Yes, Virginia Woolf. How could I spare you a photo?

She has many curious things to say about Austen, Eliot, and the Brontes (Charlotte and Emily) as well. She suggests, for example, that Charlotte Bronte had more genius in her than Jane Austen; yet, Charlotte's resentment at her restricting circumstances filled her with anger, and therefore did not allow her to express her genius clearly and wisely. Jane Austen’s mind, like Shakespeare’s mind, Virginia tells us, was entirely free. It did not resent or hate, and perhaps that is why we know so little about it.

Perhaps what makes A Room of One’s Own so powerful is its suggestiveness. Virginia repeatedly suggests that many great artists have existed and died, unable to express their genius. She even conjures up a picture of a Miss Judith Shakespeare, who, equal to her brother William in talents, is driven to commit suicide by her extreme frustration at her situation. A Room of One’s Own illuminates the tacit difficulties women faced in attempting to write in the past, and urges women of the day (1929) to be bold and create, and of course, to aquire money and a room of their own.

Awaiting the public's reception of A Room of One's Own, Virginia writes in her diary:

“I forecast, then, that I shall get no criticism, except of the evasive jocular kind… that the press will be kind and talk of its charm, & sprightliness; also I shall be attacked for a feminist & and hinted at for a sapphist…I shall get a good many letters from young women. I’m afraid it will not be taken seriously…It is a trifle, I shall say; so it is but I wrote it with ardor and conviction…You feel the creature arching its back and galloping on, though as usual much is watery & flimsy & pitched in too high a voice.”

As the introducer to my paperback copy, Mary Gordon, points out, her standars were mercilessly high: "A trifle? Hardly."

danny, your posts are fire.

ReplyDelete-Nicky