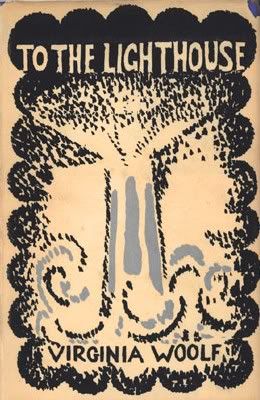

I begin with a picture of the original 1927 edition, with cover art by Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s sister. They were quite the duo, weren't they?

The margins in the latest edition of To the Lighthouse are unusually wide, as if the editor thought it necessary for some reason or other. I can’t help but fancying that they serve as a sort of picture frame for Virginia’s prose—a sort of landscape—blank, spacious, where her prose can ruminate in its own reflections, where it can think freely, without the suffocating clutter of a half-inch girdle. Indeed, I wonder! that once one sets the book down, there is not a kind of profound, under-water brooding buzzing within the closed copy. It was certainly the editor’s intention, in having the margins expanded, to call attention to Virginia’s prose, and perhaps to encourage one to respond, along these margins (with a pencil, of course), to the various impressions the novel gives, and to the questions it prompts.

To the Lighthouse is continually ranked among the finest novels of the twentieth century, and is considered, by some critics, to be 'twentieth-century novel' itself; yet, however critics choose to rank this novel among the masterworks of the twentieth century, To the Lighthouse is generally regarded, by Woolfians, as her masterpiece. But let me explain, for those of you who’ve yet to read this novel.

Consider how momentary, how elusive are the things which influence our thoughts the most. Consider those silent impressions that occur to us throughout the day, that haunt us throughout the night—that curious pinch of intuition that tells one, as one rocks peacefully on the veranda, or glares into the sun, “this is all, this is all.”

For a moment, one understands. But with the flap of a door, of a wave, of a hand it is gone. There is, of course, the other issue of communication, of reaching out for another, of trying to understand another. So we find ourselves, slighted, verging on despair, as the result of a mere glance. “I irritate her,” one suspects, or “she’s somehow compensating for the death of her father.” The most telling things about human nature are these internal suppositions—yet how capricious these are! flitting this way and that, as butterflies do. And as soon as one’s at liberty to examine these bright-winged creatures, perched on their blue-green leaves, off they go! Off! —like flick of a match! But you are probably wondering what all this has to do with Virginia Woolf. When it is said that Mrs. Woolf is one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century, it is said for a reason. For in her novels, Virginia manages to verbalize the various impressions, thoughts, and intuitive sparks that occur to us throughout the day ( this is “stream of consciousness” at its best). “She gives language to the silent space that separates people and the space that they transgress to reach eachother,” proclaims the blurb on the back of my paperback. The complexity and awareness of her prose could have arisen from no one but Virginia herself, whose profound confrontationality (I coin the word) with life, allows her to examine it from an almost objective perspective. So we see, in To the Lighthouse, pages upon pages of butterflies (those capricious sprites of one’s internal life!), pinned down, curiously labled, available to be examined at one’s leisure—no flitting involved. She is, for this reason, the most philosophical of lepidopterists. Ha!

To the Lighthouse has no plot, just as our lives have no plot. It is an internal voyage. Throughout the whole novel, however, there is always a kind of misty energy compelling readers towards the lighthouse—there, right off the shore, with all the wind! and the gulls! and the sea (how it roars!), splashing this way and that.

********************************************

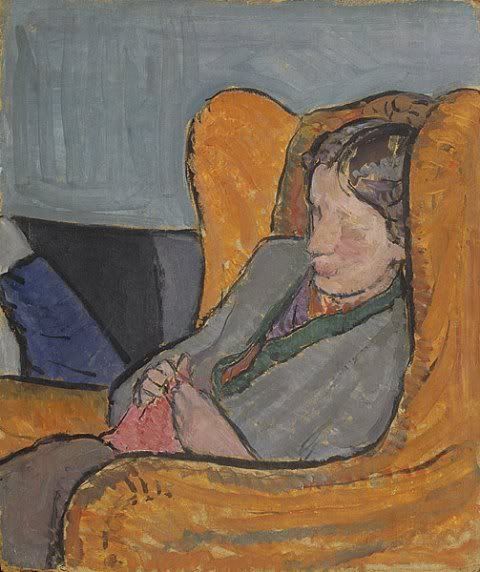

Here's a portrait of Virginia by her sister, Vanessa. Behold.

The fading of Virginia’s countenance is a modernist way of saying, “Dear, how elusive identity is!” For, couched in her banana chair, drifting casually into sleep, Virginia seems to fade out of her very own identity. Her physical features are independent from her internal existence, suggests this painting. “But what has this got to do with To the Lighthouse,” I can hear you saying... Well, very much actually. For it is this modernist compulsion to turn abstractions into tangible forms, to conceptualize the internal life that characterize much of Virginia’s work (specifically, To the Lighthouse, which is a controlled whirlwind of impressions). Virginia consciously made an effort to transcribe this kind of art (she actually refers to this particular portrait in some letter or other) in a literary form. O, those modernists!

No comments:

Post a Comment

SWEET!